And we’re back with another community release from Richard Mixin, this time it’s Landstalker!

We still have a couple more to roll out so make sure to check back next week!

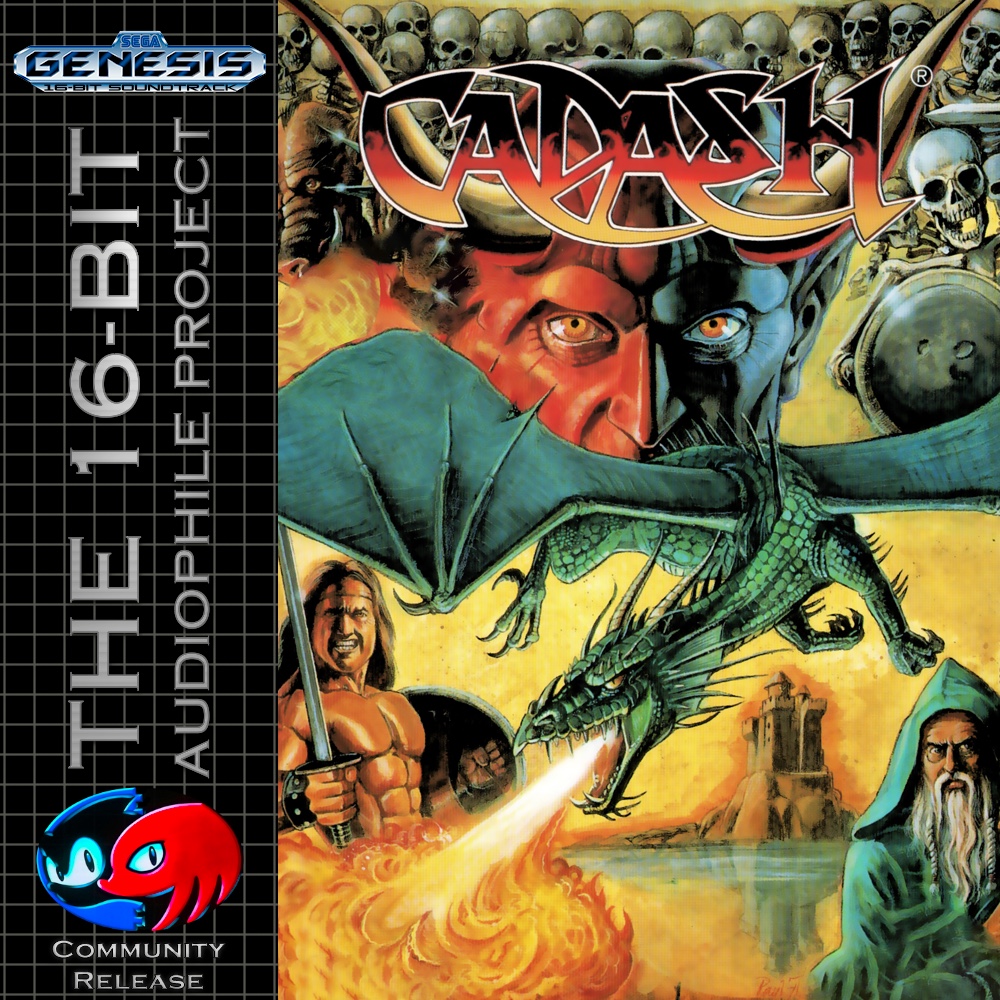

It’s time for another community release from a contributor who’s already released a wild number of games: this is Cadash from Richard Mixin!

Thanks Richard for another great release (and others which are going to come in the next week *wink wink* ).

Also, I’ll take this opportunity to update on whether we’ll be changing our logo or not: the people have spoken and the vast majority of it are for a new, original logo, which means that we’ll be at work with one of our followers who is a graphic designer to start brainstorming ideas.

Thanks as always for following us and stay tuned!

Hi everyone,

one of our followers which works as a graphic designer has graciously offered us the opportunity to have a new unique logo made for our project and redesign our album and youtube cover art.

As with most of the decisions made in the project, you, the community, play a very important role in it.

Let’s start with a bit of lore behind what we’ve been using for the last 8 years as logo and cover art.

When this whole thing started, my idea was to just make proper recordings for the “canon” Sonic games and it made sense to me to use the Sonic & Knuckles logo which I’ve always loved and thought of as pretty cool.

As for the album and youtube art, it was the work of our original graphic designer, Truepack, that took it upon himself to design something reminiscent of the game boxes and adapt it to what would be a CD jewel box cover art.

I loved the idea and, at that time, I never thought it would have blown up like this, I thought it was just a 2-3 games work and nobody would notice it, but here we are.

The main thing I wanted to discuss is that the S&K logo, while definitely being cool, doesn’t really make sense anymore and it’s not something which reminds of “audiophile grade recordings”. So I thought that something more appropriate could be made to make our project and its goal instantly recognizable.

The big issue I see in doing so, is that I believe that by now the bond between our project and the S&K logo has become unbreakable since we’ve been using it for 8 years: I swear that everytime someone looks at the S&K logo immediately thinks of our project and viceversa, we’ve become synonymous one with each other.

I’m afraid that by suddenly changing the logo to something else we might disorient people who’ve become accustomed to our old avatar.

So it’s entirely up to you to decide what to do: bear in mind that we already have releases of other, non-SEGA consoles and will definitely make more in the future.

I’ll try to put some kind of voting system up on both Facebook and Twitter, plus you can make your voice heard in our forums and Discord channel. Every opinion matters.

In case of a draw or being it very close, I’ll just play it safe and decide to just leave things as they are now.

Thank you for following us so far and stay tuned for newer developments and releases!

While we’re still figuring out the best course of action before we start making our releases again, our community has been working hard!

Katcho comes back with another contribution, Devil Crush MD!

Thank you so much for your continued efforts and we hope to see more from you in the future!

Stay tuned to our social pages as we have more community releases ready and we’ll be rolling them out weekly!

We are (almost) set up to start archiving games again.

To quickly recap where we’re standing now:

So, what’s missing?

To put it short: we need people to first check and then, where necessary, re-log VGMs.

Thankfully, some VGMs are already ok due to how the sound driver in some packs worked, but others, unfortunately, are off.

This means that at the beginning, we’ll be content just by compiling a list of games that are ok and others that need to be logged from scratch.

After that, if you thought that the process of recording and tagging files was long and boring, think again: VGM logging takes that boredom to an entirely new level.

I’ll briefly explain in very broad terms what’s needed to log a VGM, to give you an idea of the process:

Yes, this is incredibly time consuming and this is why we need help.

We have a Discord channel which is being graciously hosted on the Project2612 server and it’s pretty convenient because the server has lots of knowledgeable people how’ll be able to help you out, should you need it, to move your first steps into logging VGMs and hacking games to play the music back without SFX (although the guides I’ve linked above are pretty exhaustive).

To avoid getting the server destroyed by bots, the invite links will be shared through our Facebook and Twitter pages (or you can send me a Private Message in the forums).

If you were thinking about contributing, at this point I’d much rather have your efforts concentrated on the VGM part and I’ll be back to the recording process since it has caused much confusion among several contributors.

Plus, you won’t need any kind of recording equipment or buy anything in order to log VGMs: you just need a PC.

At this stage, even just checking the VGMs on Project2612 to see if they need to be re-logged would be really helpful.

Still, any kind of contribution will be more than welcome, as long as it follows our guidelines.

This is where we are and, again, this is absolutely too much for me alone to handle.

If you have any kind of question or doubt, please reach out via Facebook, Twitter, Forums or Discord and remember that while Discord might be great to handle instant communication, it’s pretty terrible for storing and finding information (which is why our Forums will still be left open).

Thanks everyone for getting through all those articles, I hope you’ve enjoyed them and I look forward getting back to archiving game music soon.

There’s nothing worse than trying to achieve a goal without the right tools. It makes the whole experience absolutely terrible and frustrating and the end result is seldom the best.

This is when Artemio (developer of the famous 240p Test Suite) contacted me on Twitter saying he had something he has been working on which could interest me.

The document he sent me titled MDFourier would be the beginning of a real revolution not just for our project, but for the entire world of videogame preservation, to the point were we wrote an entire article explaining what MDFourier is and how we could use it, featuring Artemio himself discussing the importance of the preservation of all forms of arts.

Thanks to MDFourier we could finally achieve what was previously unthinkable: perfect timing.

By now everyone knows we’ve been using VGMs which have their own shares of problems and limitations, but thanks to the valiant efforts of Project2612 and DeadFish Shitware, we were able to partially overcome them.

Or so we thought. Unfortunately MDFourier also uncovered a terrible truth: to put it short, almost all the VGMs in Project2612 which were ripped with KEGA (without getting too technical) had wrong timing.

We luckily managed to get around this (even without knowing it!) at the time because the DeadFish VGM Player had a feature to scale the playback speed to any desired amount, but this is truly devastating news because soon we’ll have to make a very difficult decision on whether to re-rip (most of) the entire Project2612 library or just let them be.

As I stated in the previous article, our project isn’t about just recording from real hardware anymore, it’s now about videogame music preservation and we need to do this in the most accurate way possible.

With MDFourier and the incredibly skilled community behind it, we were also able to make another huge discovery.

In the MDFourier article linked above, we discussed about what Mega Drive revision we should have used and we made some assumptions without any sort of proof.

Now, by sheer luck, we know that we’ve nailed it.

The fundamental specification about choosing a Mega Drive (which at the time of the article we completely missed) is that it should be able to play back correctly all the games available* and there are some games which won’t be played back correctly on Mega Drive VA3 and newer because SEGA decided to change the pre-amplification stage in VA3 making it a fair bit louder than the one in VA0-1-2.

This has lead to varying degrees of distortion on some tracks but, most glaringly, on Shadow of the Beast: it completely wrecked the entire game soundtrack, but on Mega Drive VA0-1-2 it plays absolutely fine without any distortion at all.

Another example of this is the Stage Clear track on Castlevania Bloodlines.

*Yes, I know, there are some games which were made specifically for the YM3438 and we’ll have to wrap our heads around this. We’ll need to make some very through research to decide what Mega Drive revision we should use for them. Most likely one of the newer Mega Drive Model 1s with the discrete YM3438 but don’t take my word on it.

So, you might ask, after all of this, where are we standing now?

In a pretty thrilling place!

We now have a new VGM logger, courtesy of blast’em, a well known cycle accurate emulator, which has been developed hand in hand with us and Project2612 and it’s absolutely perfect.

We won’t have to fear any kind of inaccuracies game-wise and VGM timing-wise anymore: we tested it thoroughly and it passed all the tests with flying marks.

So we’re all set up but there’s one very big issue: we’ll have to log all the VGMs again and, ideally, re-record all our releases from scratch.

This is something which is really disheartening but to live up to our goal, I feel like this is a necessary step. The biggest issue is that we can’t do this alone: it is just too much.

As of today, we’re still discussing with Project2612 the best course of action and what we’re going to do in the future, which is highly uncertain, as is the future of our project since it is tightly wired to Project2612.

Since this article is already pretty long as it is, there’s going to be a last part in this series which will focus on the future of our project and, most likely, a call to arms to our community (and others’) because we’re going to need all the help possible if we want to get through this.

Stay tuned as we’ll try to outline what we’re going to need and try to lay down some basic guidelines on how you can contribute to the future of our project.